In this post, we’re going to tell you exactly how to make an escape room at home.

First, making an escape room is a lot of fun. It’s not too different from playing one if you think about it. When you play an escape room you try to piece together the different clues to come up with the answers that the authors decided. When you make an escape room you try to piece together stories and puzzles to create a fun experience for your players.

Second, only by making an escape room yourself can you adapt it perfectly for your players. If you are making a game for 10-year-old children who are interested in teenage wizardry, you can make a game where they have been locked into the school’s alchemy lab and the only way to escape is by creating a secret potion. If the game is for a birthday party you can personalize the game so the story is about the birthday child who has been accidentally trapped in an alternate reality.

Finally, making your own escape room can be a great team or family activity. Unlike other types of games, such as computer games, making escape rooms doesn’t require any fancy equipment or coding skills so everybody can contribute something. You will go a long way with pens, a stack of copy paper, and a pair of scissors.

Even though making an escape room at home is not difficult, it does take a bit of time. And unfortunately, if you didn’t align yourself with the process beforehand or start off on the wrong foot chances are that you will throw in the towel sooner or later.

The good news is that we will give you a complete rundown of the process so you know exactly what to expect and where you are in the process at any given time.

Here’s how to make an escape room at home, step by step:

STEP 1: DECIDE THE SETTING

The setting is the first important decision you. It will define the tone and feel of the game as well as what props and concepts can be used in the game (we’ll come back to that). The setting consists of a place and time.

Some examples of settings are:

- Modern police department

- Private detectives office in 1940s Los Angeles

- 70’s archeological dig site

- Abandoned tourist attraction on the coast of Turkey in 1995

- The Tiberius space station in 2038

The more specific you can get, the more ideas will come to your mind that you can use in the later steps. Imagine the difference between “Tourist attraction” and “Abandoned tourist attraction outside the coast of Turkey in 1995”.

Note that the time and place also determine what items are most appropriate to use in the game. Some items will be natural in some settings and impossible in others. For example, in a game set in the present day at an office, it is appropriate to use an internet-connected computer as part of the game. However, in a private detective’s office in 1940 computers wouldn’t exist and would therefore be inappropriate to use.

Consider also that the setting has to be recreated in the play space you have available to get the players to experience it. Depending on your time and ambitions you can get very creative with this. However, to make it as easy as possible, consider settings that can be easily recreated in your dining room:

• Corporate meeting room

• The American president’s office

• Dining room in a haunted house

If you’re in a hurry you can get these settings across using very few items. For the corporate meeting room, print a fake poster with a business strategy, company values, or a pie chart. For the president’s office put the president’s name on a nameplate made from a piece of folded paper. For the haunted house buy some spider webs in a toy store and put them over the table and chairs.

Remember that your players already love you for putting together the room, they will be willing to suspend their disbelief even if you only do light decorations.

STEP 2: DECIDE THE PLOT

The plot is the second big decision. Almost all escape rooms have a plot and the challenge of completing the game is explained to the players in the form of a challenge within the plot. The plot is what motivates the players to complete the game and without a plot, an escape room would just be a thematic set of puzzles with to purpose.

The plot answers the following questions:

- What is the role of the players in the story?

- What is the situation the players are in and how did they end up in it?

- What should they do to get out of this situation?

Like in other story-based media such as novels and movies, plots can often revolve around a conflict between different parties, e.g. players wanting to escape, but someone else wanting to keep them trapped. Trapping people in rooms, however, is not the only plot there is. Here are 10 other examples of common plots from Scott Nicholson’s paper “The State of Escape”:

- Investigate a crime or mystery

- Engage with the supernatural

- Solve the murder

- Defuse the explosive device

- Be an adventurer

- Gather intelligence or espionage

- Carry out a heist

- Find the missing person

- Help create something

- Free another person or animal

Let’s say that we picked the setting of the president’s office. One plot could be that the players are secret spies from a foreign country that are visiting the White House when an alarm goes off and the president is immediately evacuated. You know that the false alarm will not be reset for the next hour, and within this time your players have to retrieve a certain document from the president’s office.

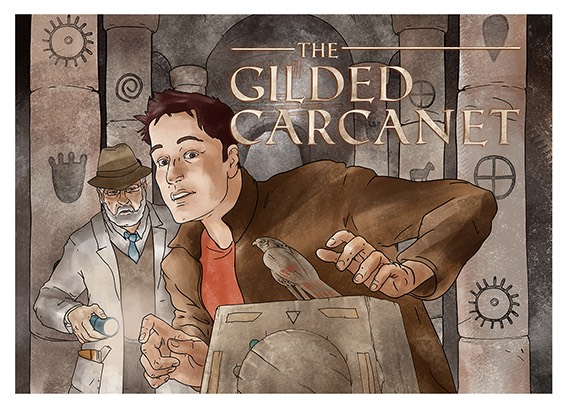

As with the setting, the plot must be delivered to your players. Printable escape rooms for home printing, such as Houdini’s Secret Room or The Gilded Carcanet, almost always deliver the plot as a written introduction to the players. This can be done in the form of a letter. In the plot example above this could be a letter from the intelligence agency that gives you the document retrieval mission.

Another common option is to deliver the plot by simply telling the players who they are and what they are trying to achieve. Sometimes this could be a pre-recorded video as well. This is common in physical escape rooms, but possible at home as well. How about recording a video using your phone and submitting it to YouTube? Then you could leave the URL on a note in the room in plain sight as the first thing your players will find even before knowing the story of the game.

Setting and plot are two things that go hand in hand and sometimes it is easier to consider them together. For example, if you have an idea for a plot there is often a particular setting that will make that plot shine. And conversely, if you have a setting in mind it will automatically give you ideas for stories that could happen in that setting.

If you need more inspiration for combining setting and plot, check out our list of the Ultimate DIY Escape Room Themes.

STEP 3: CREATE THE CHALLENGES

If you did the groundwork by deciding on the setting and plot, you are already ahead of most people trying to make their own escape room at home. Good job!

Creating the challenges of your escape room is the most fun part and where you get to be creative. However, it can also be frustrating so we will give you the best tips on how to get started.

Start from the end

As counter-intuitively as it sounds, it is the only way forward. What is the thing that the players will end up doing? Often, you answered this question already in your plot. For example, building from the plot we made before, it might be to find a secret document.

So now we have the end state of the last challenge. Now, all we need to do is to move the game one step back in time. So hitting that mental rewind button you might end up with a few different ideas:

- The document was locked in a safe and the players unlocked it

- The document was hidden inside a book on the shelf and the players found out which one

- The document was maculated and the players found the scraps and reassembled it

Just for illustration, let’s make the puzzle as simple as possible and go with the first one:

The safe is an obvious place to keep a secret document, so the only information needed by the players is the code. We could write the code on a post it and stick it to the safe. This is a very easy puzzle, but do not worry, we will solve that in the next tip.

Layer your puzzles

Consider that the puzzle we just created takes away the document (hides it in a safe) and instead gives the players a post-it note with the code for the safe. We can make the puzzle longer by continuing this line of thinking and also removing the post-it note with the code and giving the players something else instead.

For example, rather than writing the code, we could substitute each number with a letter. Suddenly the players will be unable to enter the code on the numeric keypad. And we will hide the substitution table in a drawer in the office. So just by adding one layer, we made it much less obvious how to solve the puzzle.

And, now that the substitution table is in the drawer, why not lock it and hide the key somewhere else? Maybe the key is inside a book and you can make a new clue that will help the player to find out which one? You can keep adding layers and sometimes your layers can even branch so that you get two new clues instead of one. In this case, you have two paths that you can keep adding layers to. Continue like this and eventually, you have a game.

Adding more layers to a puzzle also makes it more difficult because the players might not get clear feedback on each layer, but only in the end. Only when the player sees the safe open, they are sure that they are on the right track.

So, now you might be thinking, what is the difference between a puzzle and a full game anyway? Modern escape rooms could be considered as one large puzzle with many interconnected layers. However, I think it is more helpful to think of a puzzle as something that provides clear feedback to the player in the end, e.g. the set of layers leading up to a particular combination lock would be a puzzle.

A rule of thumb that seems to be standard in the industry is to give clear feedback once for every 6 minutes worth of play time. So a 60-minute game should have 10 locks or, if you will, 10 puzzles.

Make a flow chart

It’s a really good idea to map out the tasks your players will carry out in your escape room with a flow chart. Escape rooms are otherwise quite hard to write down and they are not too easy to remember either. You will need to give your tasks some titles such as:

- Find the key for the drawer in the book

- Find the note with the coded combination

- Unlock the drawer with the substitution table

- Decode the combination

- Unlock the safe

You can make the flow chart by hand, but since you might change it many times it can make sense to use a free flowchart software such as yEd for this. Your resulting flowchart might look something like this:

By drawing a flow chart you can also see whether your game is mostly linear or non-linear. Linear games are ones where the tasks are like pearls on a string and non-linear games are the ones that contain branches that allow players to work on more than one task in parallel. In the example above there are two branches that join at “Decode the combination” since two clues are needed to do the task and those two clues can be obtained in parallel.

This concludes the tips for puzzle creation. If the puzzle ideas don’t come naturally to you, don’t worry. We recently published a list of 24+ DIY Escape Room Puzzles that you can just grab today and there are plenty more to be found on the internet.

So to recap:

- Figure out the number of puzzles from the desired play time

- Start from the end and work your way backward

- Make puzzles with a few layers followed by clear feedback

Our ready-to-play game kits

Step 4: Play test

Once you created all the puzzles needed for your game you should make sure to test them, before hosting the game for your players.

First, you should complete the room yourself. Testing by yourself has some limitations, but if you, the designer, is not able to complete the room even with all your prior knowledge of the puzzles, then no one else will be able to. In this kind of testing, you will be able to find mistakes in your clues and props or mistakes in the overall structure of the game that make it impossible to complete.

Second, you should test on at least one person that never tried the game before. Ideally, this person should be at the same age and experience level as your players. Don’t give the tester any more information than you would give your real players.

A quick note on testing on friends and family is needed here. Your friends and family like to see you succeed so they are biased if you ask them what they think about your game. You can still do that, but take their answer with a grain of salt. A better strategy is to observe them closely while playing your game and take plenty of notes.

Before starting the game, inform the testers that they are testing a new game and if they fail to complete it without hints or fail to have a good time, it is a fault of the game and not because they are stupid. They are not the ones being tested here. Also, inform them that there will be no time limit for the test because it is more important that all content is tested.

The tester will likely be stuck at some point for some reason. If the player is stuck for more than a few minutes ask if you can supply a hint to keep the game flowing. If you didn’t prepare hints in advance you should be ready to come up with one on the spot (this won’t be too difficult for you if you made the flowchart).

In this way, lead the tester through all the content in your game, providing hints as needed and disregarding any time limit you might have put on the game. Write down all the hints you needed to give and the total time the tester spent.

After you thanked the tester and sent them on their way, it is time to make a cup of tea and take a closer look at your notes again. This time you need to ask yourself for each moment the tester was stuck and you needed to provide a hint:

Was the puzzle fair to the player?

If you only have one playtest and your play tester is in the same age group and experience level as the players, then you should make the game easier in the places where the tester was stuck. You can do this in different ways:

- Supply the hint the player needed inside the game itself

- Change the puzzle itself to make it more obvious

- Remove the layer of the entire puzzle

On the other hand, the game could also turn out to be too easy. But I find that this is quite rare in practice. When puzzles are easy for a player they turn into small tasks. So the players might skip quickly over some of the “thinking” content, but they still have fun with the “doing” content.

The only exception to the above would be if your players happen to be experienced escape room players, then they might expect a good amount of “thinking” content.

Step 5: Host the game

If you completed the previous four steps, this final one should be easy. You already know that the game itself works, but there are a few additional preparations you can make around the game to make the experience even better:

You can make additional thematic decorations for the room. Just make sure that the decorations do not interfere with the game or misguide the player because they look like they contain information. Keep it simple and avoid decorations that repeat concepts, symbols, shapes, or words that appear in your game.

To further increase immersion, add a soundtrack. This is easiest done by making a playlist on your music streaming service that lasts at least as long as your game. This way you can even let the music evolve as the game progresses, adding more tension to it.

Along the same lines, think about the lighting. For the president’s office example, daylight might be the most suitable, but if your setting is an ancient Egyptian tomb, then dim lights and candles would be more appropriate.

Finally, you should be present physically in the room and be ready to supply hints if needed. Use the same rule of thumb that if the players are not progressing for more than a few minutes you offer a hint, but of course, accept if players prefer to not get a hint.

This concludes our rundown of how to make an escape room at home. Making your own escape rooms is a lot of fun, but most people never get started on even the first step. So as a final piece of advice, just get started and use some of the tips provided here. Getting started is more important than getting everything right.